This is an article written in 2015 for my law school's magazine, and I thought this would be a nice addition for the site. The text is as published, but from time to time I do make minor amendments to the grammar and to break up paragraphs that would otherwise be tiring to read.

As written for “The Verdict” the magazine of the law school of Queen’s University Belfast (QUB), Winter 2015 issue. All rights reserved.

Introduction

Cities are perhaps the most visible and emblematic mark of human civilisation.

Throughout the entire history of the human race, there has been virtually nothing quite as prominent as the cities we have built. Cities throughout history have represented the best of their period of time, whether it may be aesthetics or just simply how we lived at that very point in time. Our cities represent the best of human ingenuity, and most of all, the constant evolution of the human race. Looking down on our planet at night from the loneliness of space, the bright spots of lights with outstretched arms like a nerve centre—Our Cities, are the surest indication to any intelligent lifeform that intelligent life does exist on this pale blue dot.

Yet today, cities are often identified with common negative characteristics such as traffic congestions, and increasing greenhouse emissions.

Most of the common issues faced by cities can be traced to a prominent root: the automobile, or the Car as we know it. Since the end of the Second World War as the world economy recovered from devastation, automobiles were seen as a catalyst to aid in increasing economic mobility, reducing travel times, as well as generally being seen as the future of transportation. Thus, entire cities and countries were built to accommodate cars, with cars being inseparable from the popular image of a major, modern city. In the United States, the role of road transportation was considered so important that President Eisenhower authorised the construction of the Interstate Highway System across the entire country. While it is true that the development of road networks have undoubtedly served as an important economic catalyst in many places, the toll that car-centric urban planning takes on cities are heavy.

This article will thus briefly explore the various aspects in which cities are negatively impacted by the implementation of car-centric urban planning.

Urban Sprawl

The most visible impact of car centric planning of a city are the sprawling suburban areas around a city core. The phrase “Urban Sprawl” provides the most literal explanation of this phenomenon: Urban sprawls are large, sprawling urban areas developed outside the city proper, usually with no sense of geometry.

The main issue with suburban areas are its relatively low density and heavy reliance on road networks. The provision of low density residential/commercial buildings over a large physical area leads to a highly inefficient use of land, as less people are housed per housing plot. For example, the amount of people housed in 500 single floor houses can be accommodated within an apartment block that probably takes up the combined plot space of 10 houses.

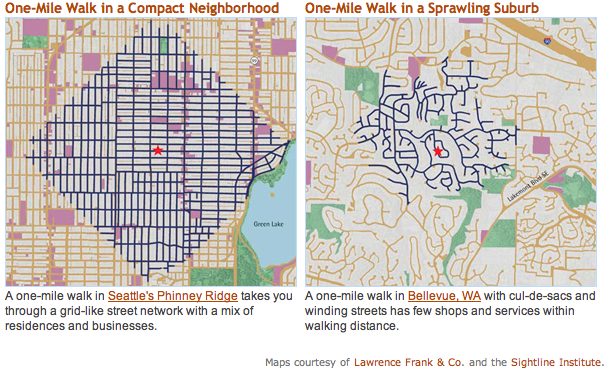

The sprawl caused by these low density developments in turn leads to an increase in distance between residential areas and services. This is because to support the sprawling mass of low rise houses, planners of suburban towns tend to prefer long main roads with smaller roads branching off it to serve individual residential plots. Given that these road networks are not only developed without any geometrical order in mind, it is not surprising that the long stretches of main roads have very low walkability due to its length, and the non-geometrical layout often sacrifices pedestrian convenience for the sake of preserving the exclusive aura of suburban homes.

As the picture below shows, a more circuitous route is needed to access Point B from Point A in a typical non-geometrical suburban layout than in a grid. Thus, the burden of transportation is inevitably placed on cars or other form of private transportation.

Public transport, on the other hand, is forced to operate at sub-optimum levels of efficiency as compared with operations in denser urban areas. Again, this is due to the low density sprawl. Buses would have to travel greater distances to achieve a decent passenger count, whereas the catchment area of a train/Metro station is either relatively small (depending on the road layout) or forced to settle for low passenger numbers due to the low walkability and low density. Oftentimes, major transit stations are forced to be sited at the fringe of suburban towns as there is no longer any space in car-centric town centres to accommodate the infrastructure.

The Road Paradox

With the automobile serving as the primary mover of urban mobility, traffic congestion is inevitable. We are not talking about localised congestion in the city core caused by narrow roads, but rather long and stressful congestion on major highways leading to and from the city centres. This seems rather confusing at first, because major highways are designed to accommodate a large number of cars at speed. What then, would cause these highways to suffer from congestion?

The answer is simple: there are simply too many cars. While it is easy for one to suggest tough anti-car policies to force a reduction in car usage, the crux of the issue is not that simple. The huge reliance on cars is usually due to a lack of alternative transport, and in turn causes the inefficient usage of road space: More road space is required to ferry 50 people in their own cars than the amount of space needed to accommodate a bus carrying up to double that amount.

In short, less space is needed to accommodate a single bus which in turn can accommodate the equivalent passenger count of 50 cars, and neither does everyone driving do any good for the environment either. With everyone driving their own vehicle, there is more carbon monoxide gas emitted (every single car) compared to if everyone simply utilised the bus or train.

We should also not forget that the frequency of buses are often negatively impacted due to road congestion.

This is where town planning comes in. If the focus of the planning has been on building more roads and widening existing one to accommodate more cars, then it is inevitable that more people will drive simply because it is too convenient to do so. Building more roads to relieve existing ones does not, in fact, relieve them. Those reliever roads will soon be filled with cars again, necessitating the construction of yet more reliever roads.

Or does it?

Induced demand is very much alive when it comes to urban planning. Contrary to what conventional road planning dictates, building more roads simply induces more people to drive. From a pedestrian and public transit user’s point of view, driving has been made the only viable form of transportation as the space that could have been used to improve walkability or to improve public transit access have been taken up by new roads.

This in turn leads us to what this author terms the Road Paradox: Space is required to expand roads, yet the expansion of roads will lead to a point in time where road expansion have used up all available space, yet more space is needed to expand the roads to meet demand. In essence, the expansion of roads negates the ability to expand the same road in the future; where in this case space is the finite resource, with traffic being the unfortunate constant.

The Personality of the City

Within the city centre itself, car centric urban planning has been known to reduce walkability as road space is maximised at the expense of pedestrian facilities. Pedestrian sidewalks, for example, are usually the main victims of lane widening, though admittedly there are many cities that feature sufficiently wide sidewalks with wide roadways as well. The focus is thus on how wide and expansive roads impact the city’s character. Wide, multi-lane roads are simply painful for pedestrians, as not only are they too big to cross conveniently, the high traffic flow also makes it more dangerous and frightening for pedestrians, much like crossing a rapidly flowing river. Conventional wisdom in many cities dictates building elevated pedestrian bridges to allow pedestrians to avoid having to deal with traffic at street-level crossings. But their usage is frequently low, simply because pedestrians do not like climbing stairs, and thus jaywalking is the only viable albeit dangerous alternative.

With walkability limited in a city, the city and its aesthetics can no longer be appreciated by its citizens, and since neither can its citizens walk comfortably within the city, there goes the character of the city. A city is ultimately defined by the people who live in it and their various activities. Thus, the city is made less lively with a lack of pedestrian activity: There is a lack of human interaction, and people would be risking their lives every time they attempt to cross a street.

As is often inevitable, road centric developments often result in a loss of public spaces as well. This makes the city less attractive and interesting to its own citizens, prompting them to seek to live elsewhere outside the city, usually suburban areas and thus completing the cycle of car-centric planning. As a result, the city ends up serving as a focal point of activity only during the day, and as night falls with the citizens heading to their suburban homes, the city becomes deserted minus a few dwellers. From a capitalist point of view, this loss of activity contributes to a decrease in profits for commercial owners in the city, which may prompt them to move their business elsewhere, thus causing a further loss of activity in the city; In urban planning speak, this is known as Urban Decay, and is a highly depressing reality when it does happen to a city. Of course, in reality a city will not be completely devoid of residents, but in most cities with a suburban metropolitan area surrounding it, the population of those suburban areas often greatly outnumbers the population of the city, and most people living in the suburban areas often work in the city and leave after work. Also, the usually high cost of living in the city means that few are able to afford a home in the city itself and thus are driven to the suburban areas, though this is another matter altogether.

The point here is that, roads are not necessary at connecting various places in a city. It is much better to build compact cities with a focus on walkability and pedestrianism, than to build a city that fully relies on roads. In many instances, walking may actually be faster and less stressful than driving, not to mention that it greatly reduces traffic congestion.

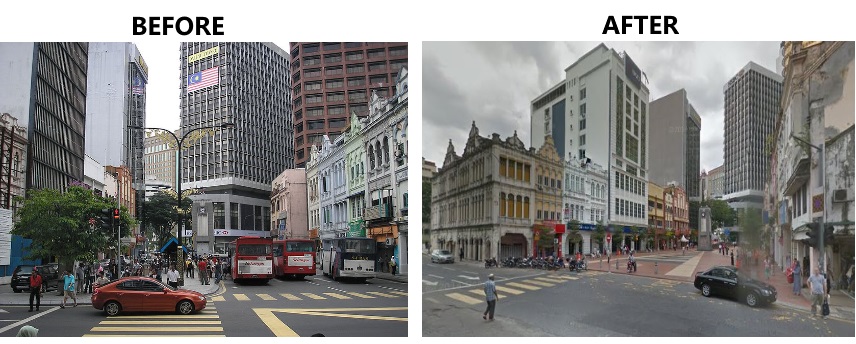

Instead of roads leading to commercial and residential plots, we can rely on pedestrianised paths to do the job equally as well or even better. Such paths have been implemented in various cities around the world. Belfast’s city centre, for example, features a highly pedestrianised shopping district, with a few roads reserved only for buses. Dublin on the other hand, has a fully pedestrianised shopping district near the Trinity College. Meanwhile in Kuala Lumpur which is a highly car centric city, the pedestrianisation of Medan Pasar (Market Square) in the historical area of Chinatown/Pasar Seni has provided the city with, firstly, a much needed public space, and secondly, a very good way to appreciate the heritage buildings fronting the square, which had previously been an inefficient bus hub with narrow pedestrian sidewalks.

In all of these places, pedestrian activity has increased as a result of a friendlier, pedestrian-centric environment, and it also happens to be a charm to walk in. In Kuala Lumpur which this author is familiar with, however, pedestrian centric conversions are still a distant dream, as the stark contrast between a pedestrian friendly environment and a car friendly one is still painfully felt when one steps out of Medan Pasar.

Reflections

Our cities are our home: How we plan and build our cities will impact how we live, and more importantly, how we evolve. While it is undeniable that the automobile has had a huge impact on much of modern economic development, it is time to rethink the way we approach city planning. We are entering an age where supplies of fossil fuels are dwindling, and having a sustainable urban development that relies less on cars and more on alternate transit is thus more important than ever.

But solely increasing investment in public transit is not the solution either, as the existing infrastructure must be heavily reconfigured in order to discourage driving, enhance the accessibility of public transit and most of all, to encourage walking again. These measures may be hard to swallow, but are a necessary step in improving the liveability of our cities, and will hopefully repel the spectre of urban decay, under which some cities are languishing.

Ultimately, the power is in our hands. None of the necessary improvements can be made if public appreciation for this issue is low, and neither will there be political will to rectify the situation. Thus, the first step in saving our cities will be for all of us to be aware of the importance of sustainable urban and transit planning.

Comments

3 responses to “How Car-Centric Urban Planning Impacts Our Cities”

Please consider changing the lines about urban sprawl. Urbs by definition do not sprawl. What we see around the city are suburbs and exurbs and the sprawling network of roads that make them possible.

Hi, thanks for your comment. I’m not entirely sure what the issue is as the definition of the term “urban sprawl” also includes suburban sprawl (low density, single use zoning, high reliance on sprawling road networks).

[…] our environments so fast that we have no interest in or means to truly notice them. This speed, some say, is what makes so many of the newer urban areas uglier than those built before the car, […]